JOE GIBBS POLITZ

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Linked resources may have their own licenses, refer to them for details.

Team Management in a Large Course

I teach pretty big lower-division courses – seldom fewer than 200 students, often (when co-teaching) more than 500. I have correspondingly large staff of instructional assistants (IAs), usually about one per 20-30 students, which means the teams range from about a dozen to as many as 40. I’ve accumulated some strategies I like for managing the work of the team.

I’ve developed and refined a lot of these techniques from co-teaching with Mia Minnes. Sophia Krause-Levy helped me understand the true potential of good Trello discipline.

In a meeting of 12+ IAs, I’ve learned that there are some things to avoid:

It’s also worth saying that the weekly meeting is really important. It’s the main touchpoint the team has to coordinate and hear the messaging about the course from me in order to set the tone for the week. So what should happen at meetings? Here are a few things I’ve found productive:

Not every meeting needs to talk about more than one aspect of the course – there are other tools for managing task updates and logistics. It’s OK if an entire meeting is dedicated just to how we will present a particularly tricky topic, or help students get started on a particular assignment, or advertise debugging resources more effectively.

There are a ton of tasks involved in running a modern CS course, especially at the lower division. There’s manual code grading, question-answering, in-person tutoring, assignment design, autograder development, live help in lecture, and generating discussion and summary slides, to name a few. I can’t do all of it myself, so a lot of it has to be delegated.

A main strategy I follow is to demonstrate how I want the task done first before delegating it. For some of these tasks, these demonstrations are best done live, the first time they come up during the course. Other times you can use some past examples to make a point. A few specific instances come to mind:

Discussion Board (Piazza) Posts: I usually tell my staff to not answer discussion board questions for the first week or so. I want to set the tone and give lots of examples, so I take that on myself. I don’t have a good, written-down guide for this, so I have to demonstrate. This gives examples of which questions should get a direct factual response, which should be answered with questions, which should be answered with a link to documentation or a course resource, which should be made private, which should be directed to office hours, what kind of tone to use to respond to irritated students, and more. After this first week, I can much more effectively delegate to a few staff members who can use the style and strategies I demonstrated to present a consistent experience.

Writing Content: When we decided to write a Stepik book and exercises for our introductory course offering, I wrote the first few chapters. Then I had the team use those chapters to write the next few and gave detailed feedback on those. After that, we settled into a weekly content-development workflow that generated a pretty decent set of interactive notes for the course. I don’t think we would have made so much progress without me providing the initial template – that’s not to say that my co-authors wouldn’t be able to produce a great book on their own, but getting the format and focus down early makes for much more efficient work and communication.

Rubric Creation: Creating rubrics for open-ended problems is challenging, iterative work. I really struggle to generate finalized rubrics before seeing some student work since I so often design new or tweaked versions of assessments and assignments. For the first few, I grade a sample of student assignments and co-develop the rubric in a meeting with my staff. We project student submissions one at a time, I discuss my rationale for creating and selecting different rubric items, and take feedback about what they ought to be. Then on future assignments I can delegate the creation of the initial rubric to one or two staff members, which we can later refine.

All of this means that there’s a lot of up-front work to training a team, but it really pays off as the quarter goes on. Having some repeat staff members can help a lot, though it’s also important to get new folks into the team to build a pipeline and avoid stagnation.

I can easily get bogged down in serving student requests for myriad issues. They might need someone to update their iClicker id, they may have to do some kind of out-of-band submission of an assignment via email, they may have a concern about a request for regrading, they may be confused about how a rubric was applied, they may be getting a bizarre internal error from an autograder, they may need coordination about exam accommodations, and so on.

It’s really important to me that I can direct the vast majority of these requests to a specific team member after the first week or two. This makes many emails from students turn from an actual task for me into a reply-and-CC to the appropriate team member (or an @-mention on Piazza). Some common roles on my teams are:

One of the critical outcomes for me in the first week of the course is assigning these tasks, demonstrating how to do them if necessary, and making sure everyone ends up with a reasonable workload on a job they are willing and able to do. This means checking in (one-on-one and pro-actively!) with those folks as their tasks get busy to make sure they have the support they need, aren’t overwhelmed, and so on. After a few weeks it’s usually possible to tell which jobs need another team member for extra help, which jobs need me to do some more hands-on demonstrating, and so on.

Having point people for different tasks also empowers the team to ask each other for help rather than me, since there’s an expert on many aspects of the course. Many grading questions can be answered by the grading manager, with only exceptional or novel situations elevated to me.

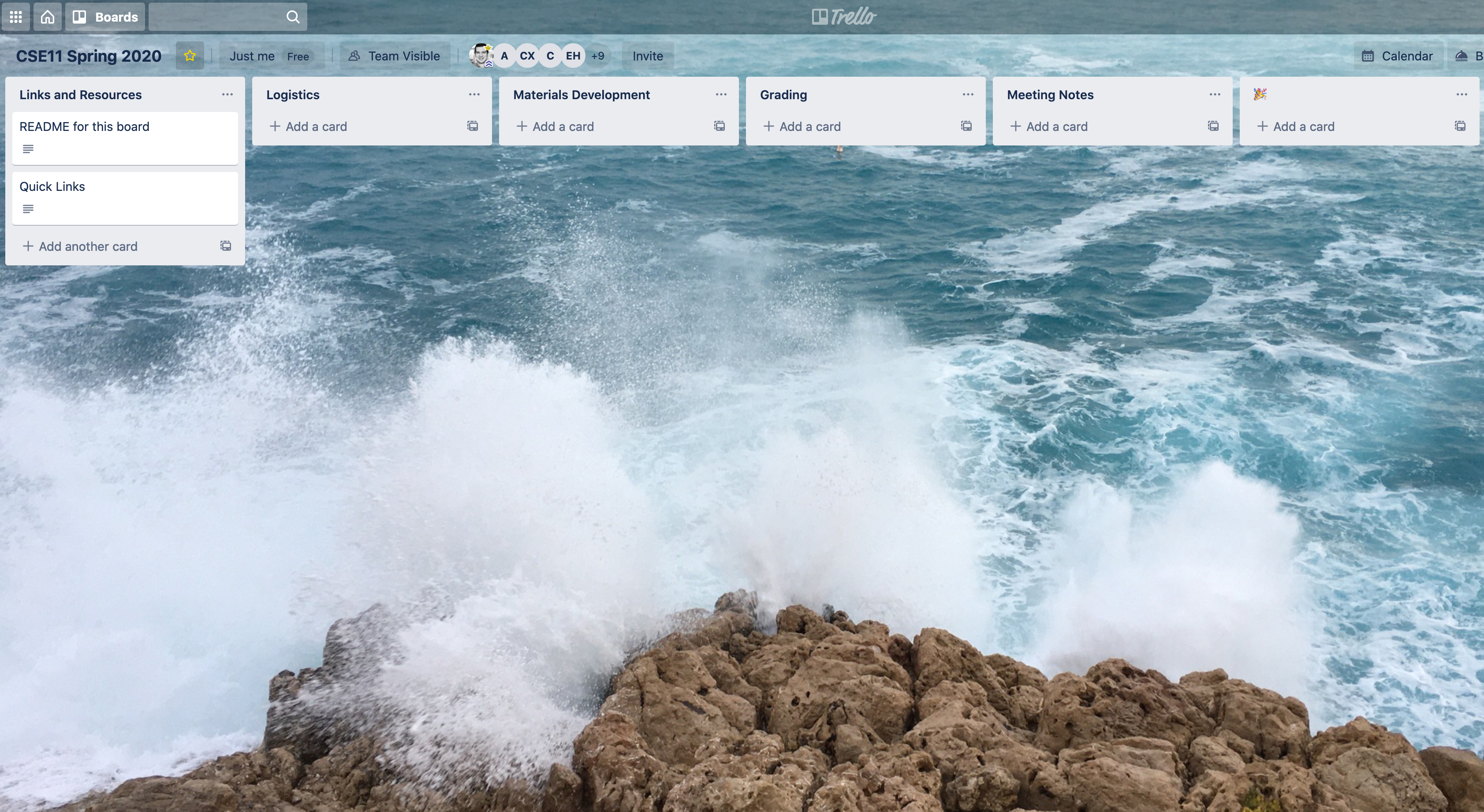

Having the delegation to individual team members requires some management. Each new task needs to be categorized and assigned to someone, and everyone on the team needs to be able to see what they’ve been assigned and when it’s due. I like to use Trello for this, though lots of different task-management solutions could work. Here’s the template for my recent introductory course:

Typically 5-6 lists are enough to categorize the work of the course. As new tasks come in, I make a new card, assign the relevant staff members, and set a deadline. The card is then the source of truth and discussion about that work – if it’s about assignment grading, it will have comments and discussion related to the rubric; if it’s about a new assignment design, it will have links to the reference solution and assignment description, and so on.

I try to stay away from email with my team as much as possible, and use @-mentions on Trello. In fact, the README card in the screenshot above summarizes how we use Trello for communication, and gives the staff some arguments for why we use it in the first place:

Welcome to the staff Trello board for CSE 11 Spring 2020.

We will be using this board to track staff tasks this quarter.

Rules to follow:

- When someone @-mentions you on Trello or assigns you to a card, you should treat it the same as if they emailed you directly. You can adjust the notification settings and your habits for how often you check the board to make sure you’re on top of things.

- Use SLACK for urgent notifications – if someone is late on a task, if there’s a bug in a released PA writeup or student-facing document, @-mention or direct message on Slack.

- Use Trello @-mentions or assigning to card to get someone’s attention in a conversation, expect that they’ll respond within 24 hours if you’re making the request Mon-Fri, 48 hours response after Friday 7pm through Sunday 7pm. You don’t necessarily have to respond by completing the task, but respond with a status update so we know where things stand.

- If you are on a card with a due date, you are responsible for understanding what you need to do by that deadline and asking for clarification as necessary.

- Make sure your account has a recognizable picture – it doesn’t have to be your face, but initials often aren’t enough for quick recognition

- Make sure your display name in your account includes your preferred and/or Webreg name, which helps a ton with @-mentioning people

- Avoid putting identifying student information directly in Trello. However, links to Google Docs, Gradescope, and so on are fine. It’s just best to avoid putting PID information directly here, and keeping it in external services.

Why use Trello? Because Slack doesn’t serve well as a TODO list, and email doesn’t work as a centralized place to share information with the whole staff. Trello is a nice solution that lets us all share information in one place, keep notifications to those who need them, and tidy up the visual clutter as we finish tasks.

There are some other handy tricks for using Trello this way:

This last point is great – once the team learns who’s responsible for what and how the board works, folks can proactively make cards and add the likely-relevant team members. This gets everything moving in a way that has team-wide ownership and accountability.

Based on the above, it probably sounds like the course runs itself after the first few weeks. And large parts of the logistics of the course do! But it turns out that it’s really hard to delegate some tasks in a course.

Any lecture material is coming straight from me, including (especially) practicing any live-coding or derivations that will happen in class, and this is usually nontrivial prep. The same goes for any paper handouts, in-class exercises, and so on. Sometimes I re-use most of an idea from a past quarter, but most require updates or new development to make sure I can navigate the wrong answers in the peer instruction questions, make a worksheet address a topic that’s part of a brand-new assignment, and so on.

More and more I’ve simply stopped trying to delegate assignment and project design aside from a few specific cases with TAs who want to do that explicitly. It’s not a particularly efficient kind of delegation, because a huge experiential skill I have is having a good mental map of which concepts will be covered at each point in the course. I can predict when we’ll be running slow or fast on the topics, have a general sense of the appropriate level of complexity, and so on. This is really hard for me to demonstrate and delegate, because it can vary a lot from assignment to assignment. I do a fair amount of new design each quarter, both for academic integrity reasons and to respond to how things went the last time, so this is where a good chunk of my time goes.

There are also many special cases that come up. In a class of 200, anything that happens to students only 5% of the time will come up about a dozen times! So I work with students who have novel situations come up for any necessary accommodations, which are often private, require varying time commitments, and teach me a lot about how to structure my courses’ policies in the future.

Finally, I actually end up doing a fragment of a lot of the tasks I’ve delegated. I answer many Piazza questions, especially the ones the staff isn’t sure how to handle, I still help debug autograders, especially when my disturbingly deep expertise with Java reflection will help, and so on. So there’s never a lack of things for me to jump in on and mentor the rest of the staff through.